Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

As families across the U.S. are sending their kids back to school, social media platforms are blowing up with parents’ proud photos of their children entering a new grade. Celebrations like back-to-school picnics, homecoming games and school supply shopping mark this societal rite of passage as symbols of growth, change and the passage of time. For thousands of parents, however, all the back-to-school fanfare serves as a painful reminder of the loss of our children to state-sanctioned violence and oppression.

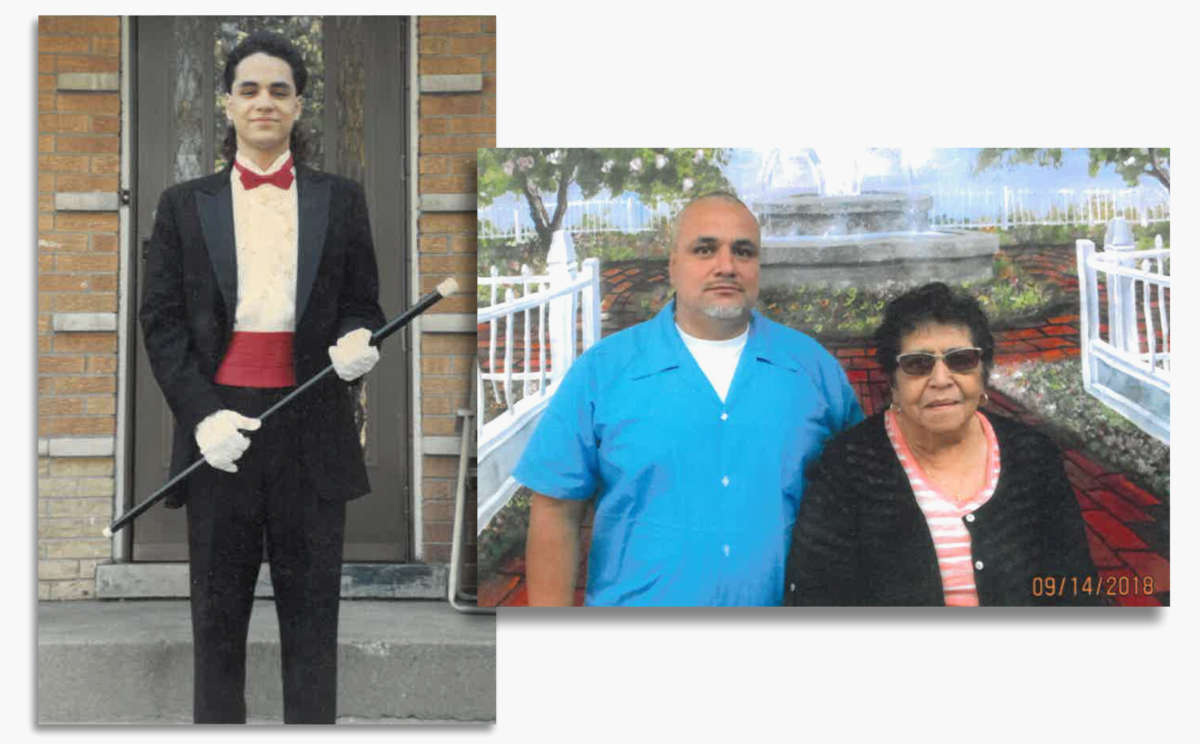

I see holidays come and go — Mother’s Day, Father’s Day, Christmas, New Year’s Eve — without my son, Robert Ornelas. For me, “back to school” especially drives home the fact that, since he was just the age of many high school seniors who are preparing for their transition into adulthood, my son has been forced to watch life through the news, from behind bars. It’s a nightmare I live with. I sleep with it. I eat with it. Wherever I go, in the corner of my mind, in the excruciating back and muscle pain I live with, in the loss of my wife, Robert’s mother who passed away from the pain — it’s there.

Because of what I and many loved ones have witnessed as the state’s use of COVID regulations as a strategy for barring us from visiting our incarcerated loved ones in prison, I can no longer see my son Robert. I understand the dangers of COVID, but the restrictions are profoundly unfair, especially as the rest of the city, state and country are operating as if the pandemic is over. Even video visits are being canceled, suggesting this is retaliation against prisoners, predominantly people of color, and not strictly a public health measure. The Illinois Department of Corrections has already kept so many of our children and loved ones locked up for decades — they took my son Robert over 30 years ago. These new discriminatory policies are further damaging to the mental health of the incarcerated people and those trying to visit them.

In 1990, when he was barely 18 years old, Robert was arrested for allegedly committing a double homicide. I do not believe the charges. Police beatings, a form of torture, were used to obtain his false confession — a traumatic and terrifying scenario that is reality for too many marginalized people and their parents in the U.S. Our family has been through an ordeal I would wish on no family.

Did my son struggle with drugs and gang involvement as he was growing up? Yes. But that doesn’t mean that he is guilty of whatever the police decide to accuse him of. In order to obtain Robert’s signature on their false confession, the police beat him and eventually convinced Robert to say that he committed the murders in self-defense. Like thousands of other people of color who are forced into false confessions, Robert was physically abused and psychologically manipulated, and I am confident he is innocent of the crime.

The men who tortured Robert, Chicago police officers Steven Brownfield and John Yucaitis, were trained in the police system created by the notorious Jon Burge. Burge was a Chicago police officer through the 1970s and ‘80s, quickly rising through the ranks because of his high case clearance rate — cases that were “solved” based solely on tortured and otherwise coerced false confessions of young working-class Black and Brown people. Burge applied heinous tactics he honed as a military police investigator in Vietnam, and trained his Chicago Police Department (CPD) subordinates in the same. This group of men became known as Burge’s “Midnight Crew,” and they went on to teach these horrific practices to others within the CPD, perpetuating the torture, abuse and mistreatment of the falsely accused and their families while deepening the city’s corruption for years to come. Yucaitis himself was part of this crew, and is associated with nearly two dozen wrongful conviction cases.

Burge’s torture methods have cost the City of Chicago over $100 million in legal fees and reparations achieved through the tireless efforts of survivors and the political movement that powerfully held them accountable. Four death row prisoners have been pardoned by the governor as result of the terror and corrupt actions of Burge and officers he trained. But the consequences of this abusive culture are still being felt today by many of my friends, including members of the collective I work with, Mamas Activating Movements for Abolition and Solidarity (MAMAS). Many of us are parenting incarcerated survivors of police violence and frame-ups. To be sure, not all survivors have loved ones on the outside supporting them. In this sense, we should also remember those whose stories don’t evoke what stories like mine might — of a parent whose child was kidnapped from their family, parent or mother. At the same time, what the children of the mothers I work with have endured illustrates how the Chicago Police Department is synonymous with corruption and human rights violations directly connected with racism and classism. This is why our collective MAMAS, with the Campaign to Free Incarcerated Survivors of Police Torture (CFIST), are demanding that the State’s Attorney Office vacate convictions for all those framed, tortured and wrongfully convicted.

Like many convicted through police violence or frame-ups across the country, Robert was sentenced to life without parole even though he was barely past juvenile status. Such a sentence, and the prison-industrial complex overall, are inhumane, and worthy of reconsideration by any society which considers itself “just.” The incarceration of youth, and the police-perpetrated abuse and coercion behind so many convictions, illustrate the brutality of the system as a whole.

The shameful reality in the U.S. is that nearly 80 percent of juveniles who face life without parole are people of color, many of them from Black and Latinx communities. Where is society’s social media outcry for them? And where are the second chances that are so often granted to their white counterparts?

This double standard becomes even more frightening as a new, highly conservative Supreme Court — stacked with three Trump appointees following his minority victory in 2016 — has indicated that a judge does not need to determine “permanent incorrigibility” before sentencing a juvenile to life without parole. This reverses years of precedent and understanding that juvenile brains are not fully developed, and disregards that we also know brains do not automatically become fully formed upon turning 18 — that age is arbitrary.

Washington State’s Supreme Court appears to have recently become the first in the nation from a “brain-development standpoint” to rule that the state “may no longer automatically sentence young adults convicted of murder to life in prison without parole for killings they committed when they were 18, 19 or 20 years old.” Illinois is considering legislation that would do much the same — those convicted at 20 years old and under would, after 40 years, have a chance at parole. Sadly, it is my understanding that the legislation would not be retroactive, meaning that it would not apply to my son — who we maintain is innocent — or others who have been sentenced prior to passage of the legislation.

I am in my 70s and will not always be here to fight this fight for my only child. With the time I have left, I not only hope the state will give me back the small comfort of safely visiting my son; I also hope more and more people will join me in the effort to free wrongfully convicted survivors of police violence like my son Robert, and all of those suffering behind bars.

My son has brought his case before the Illinois Torture Inquiry and Relief Commission (TIRC), a commission created in 2009 to review claims of police torture in Illinois and to make findings about whether or not those claims are credible. He asserts that in the state police headquarters, Yucaitis and Brownfield “cuffed his ears, kicked him in the shins, slapped and punched him several times, and squeezed his testicles.” As a result, and to stop the brutal treatment, Robert signed a statement confessing that the shooting of the two men from a rival gang in a stolen vehicle was in self-defense. Today, he denies he was the shooter. Whether the two were in a rival gang or in a stolen vehicle is separate from whether they deserve justice — they do. In 2013, the TIRC gave its opinion on Robert’s case, determining that he had presented insufficient evidence to win a new hearing. But my son has now been behind bars for more than 30 years for a crime he didn’t commit. There is enough uncertainty and sufficient evidence of improper police conduct that Robert should be released.

I remain troubled that similar police abuse was directed against our neighbor, Steve Rymus, in an effort to coerce him to make a statement against Robert. Rymus’s mother also has testified that she saw evidence of police abuse against her son and that he confirmed this to her. Abuse by Chicago police is directed not just against suspects, but against community members suspected only of having testimony — real or conjured — that could help advance the police case. As a foundational demand of the Campaign to Free Incarcerated Survivors of Torture, there is currently legislation being proposed in Illinois that would expand the TIRC’s definition of torture to include the torture and coercion of witnesses — an amendment that could make a huge difference for Robert and others like him. As a commission committed to fairly and accurately investigating claims that torture was used to obtain confessions leading to criminal convictions and providing claimants relief, the TIRC has potential to provide justice to survivors. However, the TIRC remains underfunded, understaffed and limited in scope, with a backlog of nearly 500 claims.

An abusive policing and imprisonment system has now held my son for over 30 years. Short of action by the governor, my son will spend all but the first seven months of his adult life behind bars. As a member of a working-class Latinx migrant community that is systemically and deliberately targeted by state scrutiny and racial profiling, I am aware that once youth are caught up in the system — guilty or not — there are very few viable options for relief or redemption.

In this “back-to-school” moment, I urge our society to finally reckon with its mass imprisonment of young people of color who will never have the chance to celebrate the coming of a new school year or consider what they want to be when they grow up. Instead, they will spend their entire adult lives incarcerated, in many cases, on the basis of flimsy evidence coerced by violent and corrupt cops.